Na początku potrzebne jest wyjaśnienie, co to jest odcinkowa trajektoria. Nazwa tego rodzaju trajektorii dotychczas nie była w naukach przyrodniczych stosowana. Ale tutaj będzie ona koniecznie potrzebna. Ażeby zrozumieć istotę odcinkowej trajektorii, można sobie w tej sprawie pomóc - można wyrzucić pionowo w górę albo upuścić z pewnej wysokości kamień. I właśnie ten kamień będzie poruszał się wzdłuż odcinkowej trajektorii. Wprawdzie będzie to jedynie niewielki fragment tej trajektorii odcinkowej, ale mając ten fragment nietrudno już sobie wyobrazić pozostałą część trajektorii odcinkowej. Wystarczy wyobrazić sobie, że przez środek Ziemi przechodzi na wylot wywiercony otwór. Nad otworem (z jednej jego strony) stoi wysoka wieża. Z wieży ktoś upuszcza w ten otwór kamień. Kamień przeleci przez całą Ziemię i wyleci z otworu na pewną wysokość po drugiej stronie kuli ziemskiej. Na moment zatrzyma się na tej wysokości i pomknie przez otwór w przeciwnym kierunku, aby po jakimś czasie pojawić się w pobliżu miejsca, skąd rozpoczął swój lot przez otwór. Droga, po jakiej będzie poruszał się kamień podczas ruchu "tam i z powrotem", to będzie już cała odcinkowa trajektoria ruchu kamienia i Ziemi względem siebie.

W przyrodzie nie zdarzają się loty ciał niebieskich względem siebie wzdłuż odcinkowych trajektorii. Bo nawet jeśli zdarzy się, że dwa ciała będą leciały prosto naprzeciw siebie, to nie będzie żadnego przenikania, lecz kolizja i zniszczenie ich struktury. Bardziej prawdopodobny jest ruch wzdłuż odcinkowej trajektorii dwóch fundamentalnych cząstek - centralnie symetrycznych pól. Takie dwie cząstki, niezależnie od odległości między ich centralnymi punktami, przenikają się nawzajem. To wzajemne przenikanie się jest zupełnie podobne do wzajemnego przenikania się grawitacyjnych pól Księżyca i Ziemi albo grawitacyjnych pól Ziemi i Słońca. Te ciała niebieskie przenikają się nawzajem swoimi grawitacyjnymi polami jedynie przy bardzo dużych odległościach. Gdyby w ten sposób poruszały się względem siebie przy mniejszych odległościach, mogłoby dojść do wzajemnego zniszczenia ich strukturalnej budowy.

Fundamentalne składniki materii, czyli składniki wszystkich ciał niebieskich, przenikają się nawzajem przy dowolnych odległościach między nimi. Nie czynią one sobie żadnej szkody także przy bardzo małych odległościach, bo nie mają strukturalnej budowy, która mogłaby ulegać zniszczeniu.

Po tym krótkim wyjaśnieniu można przejść do meritum. W tytule jest mowa o powinowactwie między torami ruchu w kształcie elipsy i w kształcie odcinka. Ale, na czym polega to powinowactwo, o tym można będzie się dowiedzieć po zgłębieniu treści tego artykułu. Po zapoznaniu się z treścią wiele osób zapewne będzie zdziwionych tym, że dotychczas nie wiedzieli o tym powinowactwie - pomimo że jest to takie proste i oczywiste. Ale jest to proste, kiedy już o tym się wie. W tym przypadku potwierdza się powiedzenie, że najprostsze rzeczy są najtrudniejsze do zauważenia i do zrozumienia.

O eliptycznym kształcie planetarnych orbit wiadomo od czasów Keplera i Newtona. Zgodnie z tą wiedzą, po takich torach poruszają się planety w układach planetarnych, a także składniki w układach gwiazd podwójnych. Ciała poruszają się w taki sposób, ale pod warunkiem, że inne postronne ciała nie zakłócają tego ruchu po eliptycznych trajektoriach.

Można powiedzieć, że dzisiejsza fizyka oddziaływań grawitacyjnych i astronomia traktują ideę eliptycznych trajektorii z dużym zaufaniem. Eliptyczne orbity są traktowane jako podstawowe dla ruchu ciał niebieskich. Jeśli dostrzega się pewne odstępstwa w trajektoriach ciał niebieskich od eliptycznych kształtów, to są one uzasadniane istnieniem wpływu postronnych ciał niebieskich. Do wyjaśnienia odstępstw wykorzystuje się również teorie względności. Tutaj będzie można dowiedzieć się, że eliptyczne tory orbit nie są podstawowymi dla ruchu planet - są one raczej nieosiągalnym ideałem. Podstawowy charakter można przypisać trajektoriom o zupełnie innym kształcie - o kształcie rozety.

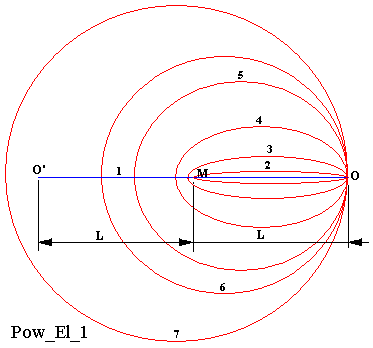

Na rysunku Pow_El_1 przedstawiony jest szereg eliptycznych trajektorii, po jakich może poruszać się hipotetyczne ciało próbne o zerowej masie wokół ciała o masie M. Odległość między tymi dwoma obiektami dla każdego z rozpatrywanych przypadków wynosi L. Kilka nakreślonych eliptycznych trajektorii to hipotetyczne tory ruchu ciała O wokół ciała M przy różnych prędkościach, jakie istnieją w momentach największego oddalenia się tych ciał od siebie, czyli przy odległości L. W tym momencie prędkość próbnego ciała O względem ciała M jest zerowa. Natomiast kierunek orbitalnej prędkości próbnego ciała jest prostopadły do odcinka OM.

O największym oddaleniu między ciałami O i M można mówić w przypadku krzywych z numerami 2, 3, 4, 5, 6. Bo odległość między ciałami O i M, która jest przedstawiona na rysunku i oznaczona jako L, dla trajektorii ruchu nr 7 istnieje w momencie najmniejszego oddalenia się tych ciał od siebie (w gwiezdno-astronomicznej nomenklaturze odpowiednikiem jest periaster). Bo w przypadku tej trajektorii początkowa prędkość ciała O (w punkcie wyjściowym O) jest już większa od tej optymalnej prędkości, przy której ciało próbne porusza się po okręgu. Przy początkowych prędkościach, które będą większe od tej optymalnej prędkości, w każdym takim doświadczeniu powstanie eliptyczny tor, który należy do innej rodziny, aniżeli ta, która nas tu interesuje. Bo interesuje nas tu rodzina eliptycznych trajektorii, dla których odległość początkowa L jest maksymalną odległością między ciałami M i O (w gwiezdno-astronomicznej nomenklaturze odpowiednikiem jest apoaster). (Będziemy tu mówić o ciałach mając na myśli takie ciała, które są zdolne do wzajemnego przenikania się przy dowolnych odległościach.)

Jeśli uważa się, że eliptyczne orbity są podstawowymi dla ruchu orbitalnego, to może pojawić się myśl, że taka hipotetyczna rodzina krzywych linii (przedstawiona na rysunku Pow_El_1) jest możliwa do nakreślenia przez próbne ciało O. Może pojawić się myśl, że jest to możliwe wówczas, gdy to ciało będzie się poruszało z odpowiednio dobraną prędkością początkową, przy początkowym położeniu w odległości L od ciała M. Rozpatrując te różne sytuacje można dostrzec pewną prawidłowość. Przy pewnej maksymalnej prędkości orbitalnej ciało O będzie poruszało się po okręgu o średnicy OO', w którego centrum będzie znajdowało się ciało M. Jeśli przy tej samej początkowej odległości L między ciałami M i O dobierać coraz mniejsze prędkości początkowe dla próbnego ciała O, to można oczekiwać, że osiągnie się ruch tego ciała po coraz ciaśniejszych i coraz bardziej spłaszczonych torach eliptycznych. Czyli że można dobrać taką prędkość orbitowania ciała O wokół ciała M, że eliptyczna trajektoria będzie przechodziła przez dowolnie wybrany punkt z odcinka O'M.

Trajektorie ruchu z numerami 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 na rysunku Pow_El_1 są tylko przykładami z tej nieskończonej ilości możliwych torów ruchu ciała O wokół ciała M.

Do takiego właśnie wniosku dochodzi się, gdy wierzy się w to, że ciała niebieskie w układach planetarnych poruszają się po eliptycznych orbitach i że ten typ orbity jest podstawowy dla ruchu planet.

W rzeczywistości, w naturze ciało próbne (gdyby takie istniało) w taki sposób nie może się poruszać. W przedstawionym wywodzie zadbano głównie o to, aby trajektorie były eliptyczne. Całkowicie został pominięty ten fakt, że przy zerowej prędkości orbitalnej ciało próbne będzie poruszało się po odcinkowej trajektorii, czyli z położenia O do położenia O' i w przeciwnym kierunku. A gdy o tym fakcie zapomni się, to nie pojawi się pytanie: Jak to się dzieje, że odcinkowa trajektoria, gdy próbnemu ciału nadawać prędkość początkową, kierunek której jest prostopadły do odcinkowej trajektorii, staje się trajektorią eliptyczną? Czy ta przemiana zachodzi w sposób natychmiastowy czy stopniowo?

Gdyby ta przemiana była natychmiastowa, to byłoby to bardzo dziwne fizyczne zjawisko. Bo przy jakiejś bardzo małej wartości początkowej prędkości orbitalnej nagle trajektoria odcinkowa ulegałaby pewnego rodzaju załamaniu i nie wiadomo z jakiego powodu nagle przemieniałaby się w bardzo spłaszczona elipsę.

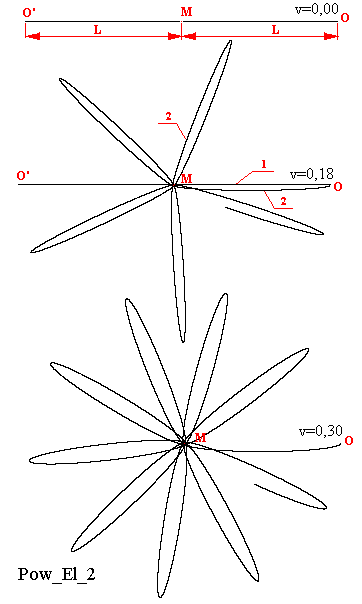

Takie bardzo dziwne fizyczne zjawisko nagłego załamania się odcinkowej trajektorii nie występuje. Trajektoria odcinkowa rzeczywiście zmienia swój charakter i stopniowo staje się coraz bardziej podobna do eliptycznej trajektorii i odbywa się to stosunkowo szybko. Ale nie jest to przemiana nagła, jednorazowa. Na rysunkach Pow_El_2, Pow_El_3 i Pow_El_4 pokazanych jest dziewięć przykładów trajektorii, po jakich mogłoby się poruszać próbne ciało O wokół ciała o masie M przy początkowej (i maksymalnej) odległości między nimi równej L. Pierwsza jest trajektoria odcinkowa, a następna - to jest trajektoria rozetowa. Bo taką właśnie postać przybiera trajektoria ciała O, gdy ma niewielką prędkość początkową o kierunku prostopadłym do odcinka (odległości) OM. Z tego powodu, że istnieje pewna początkowa prędkość, następuje odchylanie położenia trajektorii 2 od położenia trajektorii 1. Potem w pobliżu ciała M następuje ugięcie trajektorii. Ale to ugięcie nie jest wystarczające, aby mogła powstać eliptyczna trajektoria. Zamiast niej, kreślona jest trajektoria w postaci liścia rozety, a potem kolejne podobne liście.

Na rysunkach Pow_El_2, Pow_El_3 i Pow_El_4 pokazane są kolejne stopniowe przemiany rozetowej trajektorii dla różnych przypadków prędkości początkowej ciała próbnego w kierunku prostopadłym do odcinka OM, który łączy te ciała w początkowym ich położeniu względem siebie (w każdym takim myślowym, komputerowym, teoretycznym doświadczeniu). Przy początkowej prędkości v=0 j.pr. (jednostek prędkości) trajektoria ciała próbnego ma kształt odcinka. Przy prędkości początkowej v=0,18 j.pr. próbne ciało, zanim ponownie znajdzie się w pobliżu swojego początkowego położenia, wykreśli trajektorię rozetową mającą pięć liści. Przy prędkości v=0,30 j.pr. rozetowa trajektoria będzie miała już dziewięć liści.

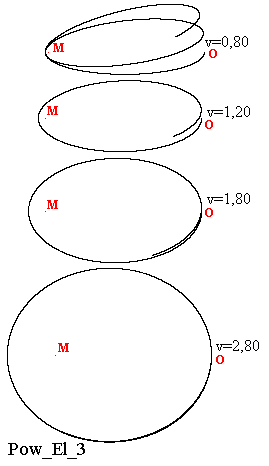

Natomiast przy coraz większych prędkościach początkowych, jak na przykład, v=0,80 j.pr. do v=2,80 j.pr. liści w wykreślanej trajektorii rozetowej jest coraz więcej i częściowo nakładają się one na siebie. Kształt liści staje się coraz bardziej podobny do elipsy, ale do zamknięcia konturu liścia, czyli również zamknięcia konturu elipsy, nigdy nie dochodzi.

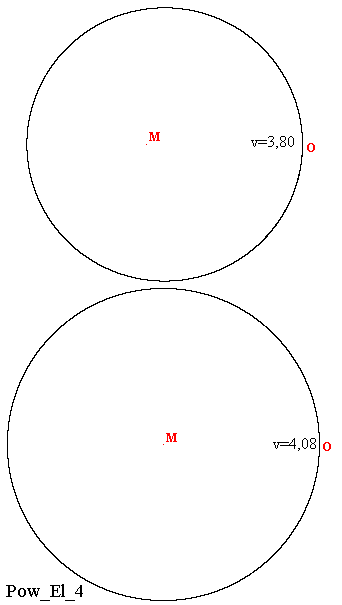

Podczas komputerowego wykreślania kolejnych takich trajektorii można dość do wniosku, że idealna trajektoria pojawia się dopiero przy takiej prędkości początkowej próbnego ciała, kiedy kreśli ono orbitę kołową, czyli w danym przypadku przy prędkości v=4,08 j.pr. Dopiero wówczas podczas każdego następnego okrążenia ciało porusza się dokładnie po tej samej kołowej trajektorii.

Jak wynika z powyższego, eliptyczne trajektorie ruchu ciał niebieskich w układach planetarnych bądź w układach gwiazd podwójnych w rzeczywistości nie mogą istnieć. Powyżej przedstawione wywody dotyczą punktowych ciał. W naturze ciała niebieskie mają pewną objętość, zatem jest to jeszcze dodatkowy czynnik, który przyczynia się do tego, że ich orbity odbiegają od kształtu elipsy.

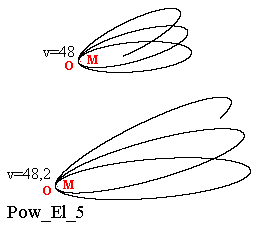

Powyżej przedstawiono orbity rozetowe, które stopniowo zmieniają się i przybierają w końcu postać orbity kołowej. Tutaj może pojawić się myśl, że istnieje taka możliwość, że orbita kołowa w wyniku dalszej zmiany, spowodowanej coraz większą początkową orbitalną prędkością ciała, przekształca się w orbitę eliptyczną. Poniżej na rysunku Pow_El_5 przedstawione są dwie takie orbity, które powstały w wyniku quasi-ewolucyjnej (opisywanej tutaj) przemiany orbity kołowej. Przemiana nastąpiła w wyniku zmiany prędkości. W rozpatrywanym przypadku prędkość orbitalna, z jaką ciało próbne krąży po orbicie kołowej, wynosi v=33,466 j.pr.

Ta prędkość została wykorzystana jako prędkość początkowa dla rozpoczęcia (w komputerowym doświadczeniu) procesu orbitowania. Została ona zmieniona w jednym przypadku na wartość v=48 j.pr., a w drugim przypadku została zmieniona na wartość v=48,2 j.pr. Na rysunku widać, że także w takich przypadkach nie dochodzi do przemiany orbity kołowej w orbitę eliptyczną. Trajektorie ruchu ciała próbnego O wokół ciała o masie M w takich przypadkach nadal mają kształt rozety.

Na tym można zakończyć rozważania nad powinowactwem krzywych linii, po jakich odbywa się ruch ciał niebieskich.Zostało tu potwierdzone istnienie powinowactwa między trajektoriami w postaci: odcinka, rozety i okręgu. Natomiast nie stwierdzono, aby do tej rodziny należała elipsa.

Na zakończenie należy zwrócić uwagę na to, że uzasadnianie ruchu perihelium planet w Układzie Słonecznym bądź ruchu periaster gwiazd w układach podwójnych za pomocą teorii względności jest bezsensowne. Taki sposób uzasadniania jest związany z przekonaniem, że podstawowym kształtem trajektorii dla ruchu orbitalnego ciał niebieskich jest kształt elipsy. Tymczasem, jak to wynika z przedstawionych zależności, podstawowym kształtem trajektorii dla ruchu orbitalnego ciał niebieskich - podstawowym, bo najczęściej spotykanym - jest kształt rozety. Przy takim kształcie trajektorii jest zupełnie naturalne to, że istnieje ruch perihelium i ruch periaster. Zatem nie ma potrzeby, aby w jakiś specjalny sposób uzasadniać to, co w przyrodzie jest naturalne i co można logicznie wyjaśnić.

Bogdan Szenkaryk "Pinopa"

Legnica, 8.11.2014 r.

*************************

The affinity of the trajectory - elliptical and segmental

At the beginning it is necessary to explain what is segmental trajectory. The name of this type trajectory has not been used in the natural sciences. But here it will be necessarily needed. To understand the essence of segmental trajectories, you could help in this case - you can throw a stone vertically up or drop from a height. And this stone will travel along segmental trajectory. Although it will be only a small part of the whole trajectory, but having this piece is not difficult to imagine the rest of the segmental trajectory. Just imagine that through the centre of the Earth passes the drilled hole. Above the hole (from one side) stands high tower, from which someone drops a stone through the hole. Stone pass through the Earth, come out on the other side of the globe and reach a certain height. It stops for a moment at that height and fly through the hole in the opposite direction, to after some time come back near the start position. This "back and forth" path, after which the stone moves, is now the whole segmental trajectory of the movement of stone and Earth relative to each other.

In nature there are no flights of celestial bodies relative to each other along the segmental trajectory. Because even if happens that two bodies will be flying directly opposite to each other, then there is no penetration, but collision and destruction of their structure. More likely is the motion along the segmental trajectory of the two fundamental particles - centrally symmetric fields. These two particles, independently of the distance between their central points, penetrate each other. This interpenetration is quite similar to the penetration of the Moon and the Earth's gravitational field or the Earth and the Sun. These celestial bodies penetrate each other, using their gravitational fields, only at very large distances. If they would move relative to each other at shorter distances, this could lead to destruction of their mutual structural construction.

The fundamental components of matter, that is the components of all celestial bodies penetrate each other at any distance between them. They don't harm himself even at very small distances, because they don't have the structural construction, which could be destroyed.

After this brief explaining we can go to the merits. The title refers to the affinity between trajectory in the shape of the ellipse and in the shape of the segment. But, what is this affinity can be known after reading this article. Probably many people will be surprised that they didn't know yet about this affinity - despite the fact that it is so simple and obvious. But it is simple, once you know about it. In this case confirms the adage that the simplest things are the hardest to see and understand.

The elliptical shape of planetary orbits is known since the time of Kepler and Newton. According to this knowledge, after such trajectory the planets are moving and also components of the systems of binary stars. The celestial bodies are moving in that way but under the condition that other unauthorized bodies don't interfere with the movement of this elliptical trajectory.

You could say that today's physics of the gravitational interactions and astronomy treat the idea of elliptical trajectory with great confidence. Elliptical orbits are regarded as basic for the movement of celestial bodies. If sees a certain derogations from elliptical trajectories of celestial bodies, they are justified by the existence of the effect of outsiders celestial bodies. To explain derogations are also used the theory of relativity. Here you will learn that the elliptical orbits are not basic for the movement of the planets - they are rather unattainable ideal. The basic nature of the trajectories can be attributed to a completely different shape - the shape of a rosette.

The figure Pow_El_1 shows a series of elliptical trajectories, after which it may move a hypothetical body with zero mass, around the body of mass M. The distance between this two objects for each of the cases is L. A few outlined elliptical trajectory are the hypothetical trajectories of the body O around body M at different speeds that exist in the moment of the greatest distance from each other, which is at a distance L. In this moment, the speed of the test body O relative to the body M is zero. However, the direction of the orbital speed of the test body is perpendicular to the segment OM.

About the farthest distance between the bodies O and M can say in the case of curves with the numbers 2, 3, 4, 5, 6. Because the distance between bodies O and M, which is shown in the picture, and marked as L, for trajectory number 7 exists in the moment of the smallest distance of these bodies from each other (in stellar-astronomical nomenclature is equivalent periaster). Because in the case of this trajectory the initial velocity of the body O (in the starting point O) is greater than the optimum speed at which the test body moves in a circle. At initial speeds which are greater than the optimal speed, for each such experiment emerge the elliptical path, which belongs to another family, than that which interests us here. Because we are interested in the family of elliptic trajectories, for which the initial distance L is the maximum distance between the bodies M and O (in stellar-astronomical nomenclature is equivalent apoaster). (We will speak about the bodies referring to such bodies, which are capable of interpenetration at arbitrary distances).

If it is believed that elliptical orbits are essential for the orbital motion, may seem that such a hypothetical family of curves lines (shown in Figure Pow_El_1) is possible to outline by the test body O. It may seem that it is possible when the body will move with suitable initial velocity, at the initial position in a distance L from the body M. Considering these different situations, you can see some kind of regularity. With a certain maximum speed, the orbital body O will be moving in a circle with a diameter of OO’, in which in the centre will be located the body M. If at the same initial distance L between the bodies M and O we choose smaller initial speed for the test body O, can expected that the body will move through the tighter and more flatted elliptical path. So, can choose the speed of the orbiting body O around the body M that the elliptical trajectory will pass through a freely chosen point of the segment O'M.

Trajectories with the numbers 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 in figure Pow_El_1 are only examples of the infinite number of possible movement paths of the body O around the body M.

A such conclusion occurs when we believe in that the celestial bodies in the planetary systems move on the elliptical orbits, and that this type of orbit is basic for the movement of the planets.

In nature, the test body (if such exist) can't move like this. In the argumentation, mainly ensured that the trajectories are elliptical. Was fully omitted the fact that at zero orbital speed the test body will be moving on the segmental trajectory, that is, from the position O to position O' and in the opposite direction. If you forget this fact, it will not appear the question: How does it happen that the segmental trajectory, when the test body have initial velocity in the perpendicular direction to the segmental trajectory, becomes elliptical trajectory? Is this change occurs instantaneously or gradually?

If this transformation occurs immediately, it would be a very strange physical phenomenon. Because at some very low value of the initial velocity the segmental trajectory suddenly would experience some kind of collapse and don't know why it suddenly changed in a very flattened ellipse.

This very strange physical phenomenon of sudden collapse of the segmental trajectory does not occur. Segmental trajectory actually changes it's character and gradually becomes more and more similar to an elliptical trajectory and this is done relatively quickly. But this is not a sudden or one-time transformation. In the drawings Pow_El_2, Pow_El_3 and Pow_El_4 there are nine examples of the trajectory, after which the test body O could be moved around the body with mass M, at the initial (and maximum) distance between them which is equal L. The first is the segmental trajectory, and the next - this is the rosette trajectory. This shape takes the trajectory of the body O when has a small initial velocity of the direction perpendicular to the segment (distance) OM. For the reason that there is a certain initial speed, occurs deviation of the position of trajectory 2 from the position of the trajectory 1. Then, near the body M occurs deflection of the trajectory. But this deflection is not sufficient to create the elliptical trajectory. Instead, the trajectory is drafted in the form of rosette leaves, and then another similar leaves.

In the drawings Pow_El_2, Pow_El_3 and Pow_El_4 are shown the next gradual transition of the rosette trajectories for different cases of the initial speed of the test body in a direction perpendicular to the segment OM, which connects the bodies in their initial position relative to each other (in any thought, computer or theoretical experiment). With initial velocity v = 0 s.u. (speed units) the trajectory of test body has the segmental shape. With initial speed v = 0.18 s.u. the test body, before again close to it's original position, will draw a rosette trajectory with five leaves. At a speed of v = 0.30 s.u. the rosette trajectory will have nine leaves.

However, with increasing the initial speed, for example, v = 0.80 s.u. to v = 2.80 s.u. the rosette trajectory has more and more leaves which partially overlap one another. The shape of leaves become more and more like an ellipse, but the closure of the contour of leaf, or also the closure of the contour of ellipse, never occurs.

While computer drawing further such trajectories can be concluded that the ideal trajectory occurs only at that initial speed of test body when it draws a circular orbit, which is in this case the speed of v = 4.08 s.u. Only then during each of the next lap, the body moves exactly on the same circular trajectory.

As can be seen from above, the elliptical trajectory of celestial bodies in planetary systems or the systems of double stars, in fact, cannot exist. Arguments presented above relate to point bodies. In the nature celestial bodies have a certain volume, so this is still an additional factor which contributes to the fact that their orbits are different from the shape of the ellipse.

Above you see the rosette orbits which gradually change and eventually take the form of a circular orbit. Here you may get the idea that there is a possibility that the circular orbit as a result of further change, caused the increasing initial orbital velocity of the body, is converted into an elliptical orbit. Figure below Pow_El_5 shows the two such orbits, which arose as a result of a quasi-evolutionary (described here) transformation of the circular orbit. The transformation was due to changes in speed. In the present case, the orbital speed at which the test body moves on circular orbit, is v = 33.466 s.u.

This speed was used as the initial velocity for the start (in the computer experiment) the orbital process. It was changed in one case, to the value of v = 48 s.u., in the second case was changed to the value of v = 48.2 s.u. The figure shows that even in such cases, there is no transformation of the circular orbit into the elliptical orbit. The trajectory of the test body O around the body of mass M in such cases continue to have the shape of rosettes.

Here we can end debate on the affinity of curve line at which the celestial bodies are moving. It was confirmed the existence of affinity between the trajectories of the form: segment, rosettes and a circle. In contrast, there was no evidence that the ellipse belonged to this family.

In conclusion, it should be noted that the justification of perihelion motion of the planets in the Solar System or periaster movement of stars in binary systems using the theory of relativity is meaningless. This way of justification is associated with the belief that the basic shape of the trajectory for the orbital motion of celestial bodies is the shape of an ellipse. However, as a result of these relationships, the basic shape of the trajectory for the orbital motion of the celestial bodies - the primary, because the most common - is the shape of a rosette. With this shape of trajectory is quite natural that there is periaster movement and perihelion movement. Therefore, there is no need to justify in some special way what in nature is natural and what you can logically explain.

Bogdan Szenkaryk "Pinopa"

Poland, Legnica, 2014.11.8.

Jestem wszystkim, wszędzie i zawsze. I wy wszyscy - także, tylko jeszcze o tym nie wiecie. Odkryjcie to na http://pinopa.narod.ru/Polska.html. Przekazuję prośbę od Łukasza - lukasz@lukasz.sos.pl : Bardzo proszę o 1,5 procent, Was nic nie kosztuje poza wypełnieniem dwóch pól w zeznaniach PIT, a mi ratuje życie. Proszę przekażcie ulotki swoim znajomym. Darowizny: FUNDACJA AVALON - Bezpośrednia Pomoc Niepełnosprawnym 62 1600 1286 0003 0031 8642 6001 BNP PARIBAS Fortis Bank Polska S.A. Bardzo ważny jest dopisek: SOSNA,711 (1,5%) Podatek: KRS: 0000270809 Bardzo ważny jest dopisek: SOSNA,711 PS. Jeżeli znacie firmę, która jest gotowa umieścić mój baner na swojej stronie z przekazaniem 1,5%, również proszę o kontakt. BARDZO DZIĘKUJĘ http://lukasz.sos.pl

Nowości od blogera

Inne tematy w dziale Technologie